I've had the pleasure of collaborating with some amazing artists over the years. One of my favorites is South African ceramic artist

Christina Bryer. Her porcelain works comprise intricate geometric patterns. They are nothing short of stunning, and spawn comparisons with some of nature's most elegant architects (i.e., Foraminifera, of course). Another favorite is

Katherine Glenday (who wrote the poem recently posted

here). Katherine's ceramic vessels are materpieces of form and make beautiful music, too. A few years ago, both artists kindly donated some "kiln failures" for use in an art/science project but, sadly, what we had in mind didn't materialize. Nevertheless, I found them handy in other ways, per below:

|

| Broken fragments of porcelain art donated by Katherine |

I like to explore the concept of scale - it's part of my work as a scientist, but it's something that humans often have a hard time with. For example, temporal scales beyond about a century ("several lifetimes") are difficult to reconcile. We can't imagine vast stretches of time, such as a few million years in the past when our ancestral hominids roamed the earth. It's easier and more comforting to reject science and think in a young earth timeframe. (That's my rationalization for certain religious fundamentalist beliefs.)

Likewise, linear dimensions often baffle the mind. Under ideal conditions, most of us can see sub-millimeter objects. Smaller objects than that, however, become a leap of faith without the use of microscopes. To help young students understand the concept of scale (and or fun), I took a piece of porcelain and ground it to dust using a mortar and pestle.

|

| It took about an hour to make dust out of Christina's pieces of ceramic |

I sprinkled this dust onto a polished aluminum "stub" and coated it with a thin film of gold to make the dust conductive. Using a scanning electron microscope, the powder looks like rocks and boulders strewn across a mountain highway following a landslide.

|

| Small pieces of dust at the sub-millimeter scale viewed by scanning electron microscopy |

|

| Micrometer dust on millimeter dust |

And with a little more magnification, we see that each piece of dust is decorated with finer dust particles which are at the micrometer scale.

|

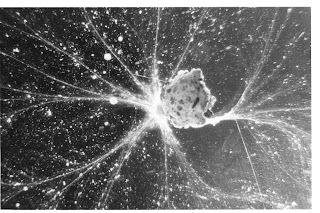

| Nanometer dust on micrometer dust |

And if we zoom in on each of the tiniest particles shown above, we see that they are, in turn, littered with even tinier particles. Using different instruments we could proceed down to the atomic scale, and with other types down to the subatomic. It's all there to be seen, and it's all

real.

In the same vein, it should be no leap of faith to appreciate that we can accurately date the age of the earth, or the age of the universe for that matter, and accurately chart the evolution of our species from life's simplest forms. Again, the evidence is all there to be seen, and it's real.

But this is not a lesson about belief. What strikes me here is that each microscopic landscape is a vista worthy of exploration and expression in the hands of artists. We just need the right tools to see with, and the skills to depict our findings in ways that are comfortable to live with. It seems so obvious that combining art and science is a powerful, straightforward way to educate young minds.